A SMALL ORANGERY IN STOCKHOLM

By: Jon Brunberg | posted: 6/15/2005 1:00:00 AM

OUTSIDE THE MAZE Grey autumn clouds are covering the skies over Northern Ireland when I finally arrive to the HMP Maze, the prison that became notorious in the late seventies because of the dramatic events that took place there. You could say that it for a few years became the main hot spot of the civil war between catholic republicans and protestant loyalists in Northern Ireland, the so-called Troubles. It was here that IRA member Bobby Sands starved himself to death in the 1980-81 hunger strikes, it was here that Billy Wright - the leader of the loyalist paramilitary organisation LVF - was murdered by nationalist prisoners from the INLA in 1997, it was here that the dirty protest took place.

The taxi driver who takes me to the prison tells me several times that the guards won't particularly like my presence and that it is prohibited to photograph here and I keep telling him that I do have a permit from the Northern Ireland Prison Service that allows me to photograph, but only outside the prison. Even though no one has been incarcerated here since spring 2000 very few visitors are allowed inside.

When the taxi driver has dropped me off and I have rigged my cameras, I start to feel a bit uneasy though. Who knows what the guards, who are certainly monitoring my moves behind that one-way glass, are thinking about my presence. After two hours of photographing, filming and carrying around my far too heavy tripod I´m done. As I was told beforehand there isn´t really much to see and what can be seen is quite depressing: endless walls of aged corrugated metal plates, concrete road blocks, junk and waste, barbed wire and one or two surveillance towers. At the same time I feel that I have achieved something just by being here: I have connected the blurry television images from my teenage past with the actual location in the present.

The Maze Prison, Lisburn. Photo: Jon Brunberg

The Maze Prison, Lisburn. Photo: Jon Brunberg

It's a few months later when I am back in Stockholm that I start to think of the Maze in terms of being a possible site for a bilateral war memorial for both sides (or rather: all sides) in the troubles. It is obviously a highly problematic spot for a bilateral memorial because it´s connected with the explosive intensity of the conflict and because the events that took place there caused so much suffering and embitterment among the population groups. Another thing that speaks against it is the spotlight on republican protests inside the prison. There were indeed as many loyalist paramilitaries incarcerated here as republican even though their activities inside the prison are less well known. Despite, or perhaps just because of, these cons the site is nevertheless interesting because it could serve as an excellent example how a specific location should be treated in the context of its symbolic value.

How would you deal artistically with the emotional aspects of a location like the Maze if you were to make it into a bilateral memorial? I turned to Sture Koinberg, who is one of Sweden´s best-known landscape architects in his generation, to get some expert advice on this issue.

Sture Koinberg. Photo: Jon Brunberg

Sture Koinbergs in his orangery. Photo: Jon Brunberg

KOINBERG´S ORANGERY

Sture Koinberg lives in a house in Enskede a few kilometres south of central Stockholm together with his wife and associate Sonja. The house is quite a typical Swedish two-storey detached villa built in the 1930ies with a modest garden that the couple has turned it into a dazzling mini-park with such odd plants for Swedish conditions as lemon trees and a vinerow. We are doing the interview in the orangery that has been added to the original house at the ground floor, which is a very peaceful and beautiful room. This day it is bathing in a warm spring light, and it feels like we couldn´t really be further away from the issues of war, mourning and remembrance that I want to discuss with Sture. But for him it is not hard to intensify the discussion from the very start. He has his own experience of war and what it can do to human beings, in this case his own family.

Sture Koinberg came Sweden together with his mother and two brothers as a refugee from Estonia in 1944, when he was only eight-year old. His father was forced to serve in the Estonian Army during the Second World War and when the Soviet Red Army invaded in 1941 they deported the remains of the Estonian Army into the Soviet Union to get it out of their way before the upcoming battle with the Germans. In 1943 the Estonian militaries that survived the camps were forced to fight with the Red Army. Even though Sture Koinberg´s father survived the war it would take over twenty years before Sture would see him again. The family was never reunited. An iron curtain separated them.

"I think many with me who experienced WWII are severely depressed when we follow the events in a country like former Yugoslavia and elsewhere," says Sture. "When we hear of events such as the recent Madrid bombings it reminds us of other terrible atrocities. I believe that World War II is still the big trauma of our time".

Sture Koinberg´s own traumatic experiences as a child has given him a special relation to war memorials and he has visited many on his numerous travels. "When I visit the type of memorials that have been erected in all small English towns from WWII, I often say to myself that these were the boys that sacrificed themselves for us so that we can live in a democracy today. It´s healthy to think about that sometimes. At the same time it´s very upsetting when you realise how many boys from these villages that actually died in the war."

Sture Koinberg says that we must be reminded again and again of the atrocities of war and that war memorials can play a significant role in that process. "There are some memorials, like the Vietnam Wall in Washington, which are very powerfully designed. I think it will take a long time before that particular memorial loses its force. Another example is the US Army´s war cemeteries in Italy where hundreds of thousands of soldiers are buried under endless rows of white crosses. These places are so horrendously scary that it´s impossible to forget them once you´ve visited".

Sture Koinberg studied architecture at the Royal Academies in Copenhagen and Stockholm in the sixties and opened up his own office in Stockholm a few years after his studies. The office grew rapidly because of the building boom in the late sixties and beginning of the seventies, which was the result of the Swedish Government´s so-called "Million Program". The Million Program was a project of gargantuan proportions that resulted in two million flats being built over a period of twenty years to a population of eight million. All effort was put into the construction of cheap high-rises and none to create decent outdoor environments for the inhabitants. When the Government realised that this was a serious mistake Sture Koinberg´s office got numerous commissions. He describes that time in the history of the office as being "fantastic". The firm would often establish temporary offices in the suburbs and design the green environments together with the inhabitants, and plant together with them in the spring and fall. During this time Sture Koinberg´s landscape architect´s office grew to be the biggest in Sweden. After the Million Program period, which lasted for almost ten years, the office continued to work in all areas of environmental design from large-scale projects such as the Globe Arena in Stockholm to more odd projects such as the creation of a typical Swedish summer meadow for one of the members of the famous pop group ABBA. Sture Koinberg´s office has also been involved in the creation process of at least one memorial project, Raoul Wallenberg´s Square in central Stockholm, which was designed by Aleksander Wolodarski and includes a group of sculptures by the artist Kirsten Ortwed.

The Maze Prison, main gate, (c) Northern Ireland Prison Service. Published with permission.

The Maze Prison, interior: cell, (c) Northern Ireland Prison Service. Published with permission.

THE MAZE PRISON

After discussing more general aspects of war memorials and gardens as a healing force we turn to the task to transform the Maze prison into a national bilateral war memorial, in remembrance to all the 3300 people that were killed as a result of the troubles. The memorial would include the names of killed paramilitaries, politicians, civilians, police and militaries since the troubles started in 1969.

The history of the Maze Prison is short but eventful. It was built on a military airfield and ready to use in 1971. The prison is located a few kilometres outside the small town Lisburn some 20 km south of Belfast in a flat landscape, which is quite typical for this part of the country. The Maze was seen as the most modern high-security prison in Europe when it was built and was considered escape-proof. A visitor has to pass several layers of walls, fencing, watchtowers and guarding stations before she can enter the central pentagonal area where the compounds are located, popularly called the H-Blocks because of their H-shaped design. An imprisonment campaign by the British in the mid seventies led to the result that a significant part of the conflict between different paramilitary groups and the prison authorities continued inside the prison walls and reverberated far outside the prison gates.

The most well known campaign outside of Northern Ireland in the Maze is probably the hunger strikes that was conducted by IRA prisoners in 1980-81, a campaign which gave the paramilitary organisation its most celebrated martyr: Bobby Sands. The authorities decided to vacate the Maze in 2000, partly as I understand because of the symbolic value the prison had gained for different groups during its short history, but also as the result of a general amnesty for paramilitaries after the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The future of the prison is not yet decided five years after it was closed and the subject has from time to time been fiercely debated in Northern Ireland. It is indeed a delicate issue for any politician in the Northern Irish assembly Stormont to propose a final solution to the future of the Maze because it will most certainly be disregarded by parties representing the other side of the conflict, and might in the worst case even spark further hostilities. It seems like the Maze has to be a "sleeping dog" for yet a while. There have been interesting proposals though over the years, among them to turn the prison into a museum, which is perhaps not too far away from the scenario I presented to Sture Koinberg. [1]

THE PROCESS AND THE PEOPLE

For Sture Koinberg it is of utmost importance that relatives and other concerned parties are invited to take part in the creation of a war memorial of this kind and that it has to be done in a democratic process. "Many have to be willing to contribute to a solution to the conflict. The people who were there and the relatives have to lead this process because they´re the victims. If they have the strength to, that is. It has been evident that many people having these traumatic memories aren´t able to live a normal life if they have to talk about them over and over again." Sture Koinberg also stresses the great importance that the people concerned can suppress their aggressions. "I have personally been looking down into the boots of both Russian and German soldiers but I´ve tried to avoid transferring any aggressions to my children. If you start doing that, which was certainly the case in former Yugoslavia where generation after generation were fed with new aggression, it´s a huge risk that new conflicts will erupt. It will of course be very hard for those who has engaged deeply in the conflict to break their patterns of behaviour but somehow these groups have to bring themselves together and start to discuss their own problems." Sture shrugs. "I guess that it is an easy thing to say when you´re standing in a small orangery in Sweden. It´s in fact impossible to tell these groups how they should solve their situation!"

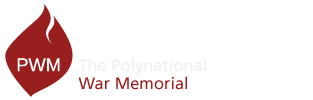

Unionist paramilitary poster, see copyright Disclaimer.

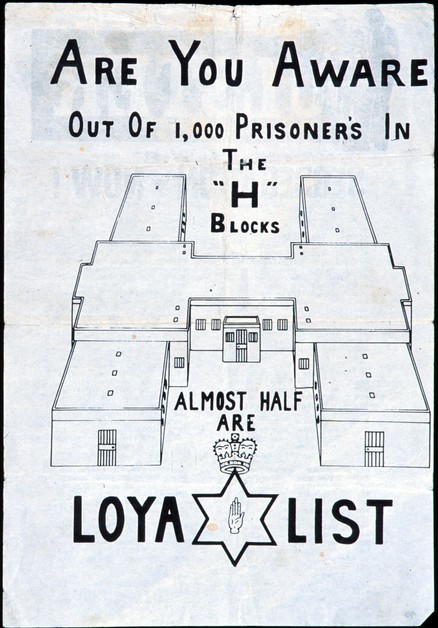

Republican Poster, see copyright Disclaimer.

HEALING OR PERMANENTING?

If you are going to build a memorial on an existing spot with a strong symbolic value how should you relate to the history and the traumatic experiences connected to that space? "One of my strongest experiences concerning the Holocaust was when I visited one of the concentration camps. I realised then how important it was that the place with its buildings was preserved. It would have been impossible to imagine what happened there if the location´s ´soul´, if you could talk about such things, wasn´t preserved for coming generations, even if it is a brutal soul that displays the evil side of man. Of course you´re going to experience things much more intensely when you´re walking on the same concrete path that was the last thing many people saw in their lives." "We took part in an competition many years ago for the rebuilding of the Långholmen Prison in Stockholm and many people involved in the process had the opinion that the prison was so infected by human misery that it should be demolished. That question is highly relevant also in this case. Is it so that there is too much misery connected with this particular location that you have chosen, so that it must be razed to the ground? By asking that question you are bringing the matter to its head. I´d say that remembrance in this case is more important than demolition because the events can´t be erased from people´s memories anyway. I believe that it might be good for our generation and several generations to come to be able to physically experience the events, the consequences for the people that engaged in the conflict, and the place where they spent so many years." Sture continues: "It must not in any case become a monument for one of the sides. If only one of the parties in the conflict had been incarcerated in this prison I´d be tempted to say that it should be demolished but since both sides were represented it gets a symbolic value, because it would be possible to describe the healing process." "Let´s say that we are going to preserve these buildings", Sture Koinberg continues. "What is the purpose for doing so? Is it with the purpose to heal or to permanent the conflict?" This is a highly problematic issue, which is crucial to the Polynational War Memorial project, and one that needs to be carefully considered. What if a war memorial for both sides of a conflict rather than inspiring to reconciliation instead deepens the conflict and promotes bigotry? It is just too easy to see a peace process being blown to pieces by endless discussions about who should and shouldn´t be included in the list of names in a future memorial, what kinds of sentiments the memorial should express and how it should be designed. Even the use of colour in an inappropriate way could provoke conflict. The important question here is whether the expressions of cultural difference in the form of emblems, slogans and colours that the parties are using in order to keep their communities together and exercise power over should be allowed into a memorial of this kind. These symbols may permanent the sentiment among the population groups that there are indeed strong cultural differences and that a reconciliation process can therefore never be successful. It is perhaps not surprising that many contemporary war memorials are stripped of cultural symbols.

THE MEMORIAL AT THE MAZE

I am at this point of the interview quite curious what means and solutions that Sture would use as a landscape architect to create a memorial at this particular site. "If we assume that nature can contribute to a healing process of human wounds suffered in conflict with other humans, I would suggest the possibility to create a contrast effect between the cruelty symbolised by these compounds and the comfort and relief of a surrounding landscape. That is a contrast effect that could be achieved with artistic means." He invites me to sit down at the big table in the middle of the orangery and rolls out semi-transparent architect paper over a blueprint of the prison area with outlines of the H-shaped prison compounds, which I gave him when we met the week before. He starts to make a rough sketch using coloured felt-tip pens while explaining his ideas. "Since the prison compounds are built in the middle of this open field I would suggest that the surrounding area is cleared so that the compounds are enclosed in something that could be described as a green island in the middle of the field. The fencing that runs around the compounds should also be preserved as the outer border for the memorial area. There should only be one entrance to the memorial and you´ll have to walk over the field to get to it." "Now comes the difficult question. Should this be a green environment and if so why? If we´re making it a green island it could illustrate the healing process as in the old saying ´time heals all wounds´. We can accentuate the illustration of the temporal aspect if we plant all trees at the same time, and even further by sowing seeds or acorn. I can imagine the planting process being done by school children to symbolise a new era of peace. That would be truly amazing. One school class could be responsible for one or several trees that they could take care of and follow over several years, perhaps all their lives. The responsibility for these trees could even be inherited by their children in the future." "On this location there are several buildings and I don´t believe that all of them should be preserved, perhaps only one on each side of this dividing field in the centre." He outlines the two H-blocks he´s referring to. "These compounds should be converted to educational premises for peace research and exhibitions. If other buildings have to be added they must be designed in a different way." Sture Koinberg continues with the field in the middle of the draft that divides the two groups of H-Blocks. He assumes that this field divided republican and loyalist prisoners from each other, something that sounds reasonable even though I do not know whether it actually did. "The middle axis that parts the two sides is a big artistic challenge since it could visualise the healing process. /.../ I think that the existing streets should be preserved and perhaps broadened. They will become an important symbol for the bridging of the conflict by connecting both sides." He draws a series of paths connecting the two free standing H-Blocks. "These streets, or paths, could be designed to have different symbolic meanings. I would say that the kind of path that symbolizes the peace process has many obstacles and is quite crooked. Other roads are troublesome and pass water or rock. One might even be a dead end road. Hedges or rows of trees could be planted along these paths as in a traditional English park. I can imagine a hill on the northern end from which you could have an overview over the area and all the various paths." Sture Koinberg has another thoughtful concept for me up his sleeve that doesn´t only include the conflict in Northern Ireland. "There have been so many horrible wars in this part of the world. It would have been one thing if it were only the Irish and the British that have to reconsider their actions! Let´s say that the prison was converted into a university for peace research. In this case you would get a completely different type of architecture where all compounds have different functions as being parts of that university." He points to the wall that runs in a pentagon round the core prison area. "This wall or fence could be transformed into a walking path, let´s call it ´The Path of European Suffering´. It would be designed so that there will be only one way to enter and exit, which means that once you´re inside there are no shortcuts and you´ll have continue or turn back." Along this wall there would be a permanent exhibit with text and images documenting the atrocities and the suffering of this century. "Each nation would be responsible for their own design since all peoples have their own aesthetic tradition. Even Sweden could contribute with information and memorials concerning such events as the expelling of Baltic ex-soldiers to the Soviet Union and the work of Raoul Wallenberg." He pauses and then concludes: "Once you have walked trough this road you will be so terrified that you realise that this path should not be followed in the future. This place should perhaps not be idyllic and I must admit that there is always a risk that I, as a landscape architect and garden architect, will be tempted to do that. If such a design becomes an idyll you have probably missed the point. It is good if the exhibit includes a hopeful and educational part but I think that you first have to make a trip trough the hell of suffering to get there." EPILOGUE A war memorial in its traditional form is in a sense a symbolic continuation of the war itself with the function to comfort relatives and comrades and to hold a people or nation together. A multi- or bilateral memorial as the proposal that has been discussed in this article may have the same functions as the traditional ones, but it strikes me that the controversies that would inevitably follow a design proposal of this kind could actually in itself be turned into a democratic and healing process if these emotions are taken care of with sincerity and openness.

-------------------------

NOTES [1] A very informative report from a conference on the possibility to establish a museum at The Maze held in Lisburn in June 2003: A Museum at Long Kesh or the Maze?

-------------------------

EXTERNAL LINKS

The web site for Sture Koinberg Landscape Architects:S.Koinberg Landskapsarkitekter AB