AN INTERVIEW WITH PETER TONKIN

By: Jon Brunberg | posted: 7/5/2004 1:00:00 AM

This interview with Australian architect Peter Tonkin was made in the office of the architect bureau, Tonkin Zulaikha Greer, in Sydney in Nov 2003. Peter Tonkin has designed several war memorials, often in collaboration with artists, for example the Memorial to the Australian Forces in the Vietnam War, in Canberra, and the Memorial to the Australian Forces in WWI and WWII, in London.

From the top of Anzac Parade where the Australian War Memorial is located you can see the Australian Parliament, Capitol Hill, only a kilometre away. Along the parade, which is a couple of hundred meters long, several war memorials have been erected on each side. These memorials have been built to commemorate Australian soldiers and other military personnel who fought in wars all over the world during the 20th century, and the formal expression varies consequently. Australia is still a part of the Commonwealth, with a General Governor as a head of state who is appointed by Great Britain, and the nation has sent troops to many of the conflicts that Great Britain has been involved in. At the end of the parade there are some empty "slots", spaces that are waiting for the next war to begin and end, and the next memorial to be designed and built. Somewhere halfway down the parade you´ll find the War Memorial to the Australian Forces in the Vietnam War that was built in 1992 on commission from veterans organisations and the Australian Government.

The exterior of the memorial is constructed of three freestanding concrete walls or stelae that are slightly twisted and form an open-ended, steep pyramid that is 9.5 meters high. The stelae are placed on a low triangular podium of granite surrounded by water basins. Seven metres above the podium floor, suspended from the internal walls of the three stelae is a ring made from 24 sawn black granite segments, each supported by three suspension cables. One interesting detail is that inscriptions of the names of all the Australian soldiers that died in the Vietnam War from 1962 to 1978 are contained within one segment of the granite circle. The presence of the names was obviously seen as a healing element of such importance that it was included in the very design, even though the visitors cannot see it.

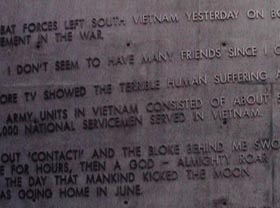

The heaviness of the twisted, inclining walls and the hanging granite ring gives me a slightly eerie feeling of the construction being instable as I enter the memorial from one of the ramps. Two of the walls are covered on the inside with black granite. On the wall facing the parade is an image that is larger than life that was sand-blasted in the granite, which shows Australian soldiers at a helicopter landing strip in the jungle, waiting to being flown out of a military base. The wall to the right is inscribed with quotes in relief in the stone, sentences cut out from interviews with anonymous soldiers and officers. It is a sombre day with heavy grey clouds hanging in the sky and the rain pouring down occasionally. It is not difficult to feel the heaviness of the history of war weigh on your shoulders. On Anzac Day however, the parade is usually filled with tens of thousands of veterans and spectators that gather to commemorate their fallen comrades and relatives.

Two days later I´m visiting the architect Peter Tonkin in his office in Sydney, bathing in the sun during the first hot weeks of summer. He is one of the founders of the architectural firm, Tonkin Zulaikha Greer, and has been involved as a designer in several war memorial projects. Peter Tonkin has just returned from London where he attended the opening of a War Memorial to the Australian Forces in WWI and WWII in Hyde Park Corner designed by TZG Architects.

I´ve made an appointment to interview him about his work with war memorials and his thoughts on multilateral solutions. He shows me several sketches from the creation process of the Memorial to the Australian Forces in the Vietnam War in Anzac Parade, which was a joint project between him and sculptor Ken Unsworth. They got the commission by winning a two-stage competition in which the jury was composed of some artists, architects and representatives from veterans organisations and the National Capital Planning Authority in Canberra.

The memorial was finally built, with few changes, but Peter Tonkin says that the whole process was quite traumatic due to the lack of sufficient funds and time pressure, and that he told himself that he would never build a memorial again after the first projects were done, but TZG Architects have since participated in other competitions for war memorials, of which the most recent is the memorial in Hyde Park Corner in London. Peter Tonkin explains why he finds memorials so inspiring to work with. "I enjoy it because it becomes purely about architecture and meaning and you can step back a little from all those functional aspects that make a lot of architecture constrained, but also because the clients often want an expressive work of architecture whereas many building clients want a purely functional building and you almost have to slide the architecture in without them noticing. In memorials the functional aspects are generally not too difficult”. He says that the possibility of simplifying the design and limiting the number of materials enables him to intensify the power of his ideas, and that this is something quite unusual compared to other architecture. He explains that another interesting factor is that war memorials "are objects that have to carry meaning for a very long time”. And that is something which “challenges you to verbalise and determine very clearly what kind of message you want the work to portray”.

I can imagine that the emotional aspect in the creation process of a war memorial must be radically different from that of a house or public building. War memorials are made for people who have been severely traumatised, the memorials are there to heal, which also means that they must bring the trauma out into the open through remembrance, something the architect must take into account in the design process. In this case, as in many other cases in the Western World, the memorial was initiated by and substantially paid for by veterans organisations through public fundraising, and the affected group, and the users of the memorial, would have a strong influence on the process of its creation. Peter Tonkin points out that the Vietnam veterans are still in their forties and fifties and their memories of the war are thus quite fresh. How does a designer deal with these strong emotional aspects?

It was clearly very difficult for the designers to predict how the veterans would receive the proposal and Peter Tonkin tells me that he didn´t really expect them to like it, but that their only option was to create a design that they themselves liked and not to compromise. He shows me a sketch made to explain what kind of monument they wanted to avoid, a frontal, realistic monument, like a bronze statue. Their design is rather the opposite of this since it embraces the visitor and creates a room for contemplation rather than being an object that you stand around and view from below. Rather than being the state´s monumentalisation of war, it is a church-like room for remembrance.

It is also important to remember that this is a memorial created for a nation that did not win the war and the function of the memorial is to express grief and reconciliation rather than triumph. As I understand it, there was also the requirement that the design "represent the controversy at home" (1), in order to express the division of the society over the Vietnam War.

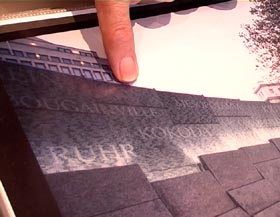

The Memorial to the Australian forces in WWI and WWII in Hyde Park Corner in London has a slightly different background. The wars fought are long gone and the loss immense. Even though the allied forces were victorious, the memorial is not triumphant in its expression. It was designed to be able to accommodate the 15,000 veterans who were expected to visit the memorial on Anzac Day each year. The brief furthermore stated that the monument should be identifiably Australian and the design team solved that by creating a broad landscape form. The monument, which is made of black granite and water, was designed as a curved form that was placed in one of the corners of the park as a natural continuation of a slope. The memorial does not include the names of the fallen. Instead the names of the 27,000 cities and towns where the Australian servicemen were born are inscribed in the stone. By setting some of the letters in bold, 44 names of places are spelled out in another layer of text, places where battles were fought that the Australian army - the “Anzacs” - participated in.

I ask Peter Tonkin what he thinks of the possibility of creating multi- or bilateral war memorials and he takes the Hyde Park Corner Memorial as an example: "We were very adamant that this [memorial] would not be seen as one of those simplistic statements of victory, as a triumphal arch might be. A triumphal arch can only have one meaning, whereas something like this is very much not about the pomp of victory or necessarily the tragedy of loss but has something to do with both sides. It doesn´t overtly reference the enemies in WWI and WWII, but it gives you the sense that this was a tragedy in the past, and rather that that tragedy is over, that the water has cleansed the memories of these terrible, terrible battles, where just as many Germans, Italians and Japanese died as allies. They´re not victories by any means, they were just places where many people died. The thing that ties it directly to the one side is the names of the birthplaces of the Australians”.

He also describes the Vietnam Memorial as keeping something of that two-sidedness that in a subtle way brings up the question of an unresolved conflict. He says the main purpose was to resolve and not to monumentalise the lack of resolution.

So how would he see the possibilities of designing bi- or multilateral war memorials? "It would have to represent a level of concord, of coming together between the two sides. You will have to get them to agree to the creation of a single thing, so that it would be a truly practical manifestation of a sense of agreement between them. So, of course it will be possible, you just have to write it into the brief. I try to mentally run through memorials trying to find some that have a bit of that bilateral or multilateral sense but there aren´t very many. Some of those peace-type memorials might, but they try to state peace as an antithesis of war, and not to resolve the issues of war. They just monumentalise peace in opposition to war. To design something that has more of a sense of coming together in war is obviously difficult but it is the task of the designers to try to make durable an expression of those ideas”.

I bring Peter Tonkin´s optimistic attitude with me as I leave his office, and I certainly need it because the project that I am about to initiate could easily take on enormous proportions, and I cannot yet imagine what forces I will encounter on my way. At the same time it reminds me that the structures and forces that dominate the world in the form of nations, supranational organisations and empires, are only man-made constructions, structures that will transform over time. It might not be long, perhaps, before a polynational war memorial is as natural as the global air transport system is today.

***

Notes:

(1) War memorials in Australia, http://www.skp.com.au/memorials/pages/00005.htm

Links:

About the Vietnam Memorial in Canberra

About the WWI and WWII memorial in London

The web site for TZG architects

Part of the series ''Issue #1''

The first series of features presented on war-memorial.net