OUR TRAIL OF THE TROUBLES

By: Jon Brunberg | posted: 6/16/2004 1:00:00 AM

An article about Hillary Gilligan's intervention "Our Trail of the Troubles", made in Belfast 1996.

In doing preparatory research for the Polynational War Memorial I have discovered just how few bi- and multilateral war memorials there actually are in this world. This is perhaps not too surprising. Built into the power mechanisms of a sovereign nation-state is its rejection of cooperative platforms with its former enemies. The process of creating such a memorial on a governmental level will have to be a painstaking one that could take years if not generations.

Let us take the peace process in Northern Ireland as an example where several proposals for the bilateral type of war memorial were suggested after the ceasefires of 1994 (1). The peace process must of course first be negotiated, and only when the advantages for both sides of manifesting that agreement with the creation of a bilateral war memorial were obvious could it eventually be commissioned.

The advantages of a bilateral memorial in this case could be to bring the two sides together again after years of hostilities and mistrust. It could help to reduce the alienation from and demonization of "the others" which in turn would stimulate both economic growth and living conditions for the benefit of both sides. A bilateral war memorial could actually have been commissioned in Northern Ireland had the peace process been a smooth and easy one, which of course wasn’t the case. Since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the peace process has stalled, continued, progressed, been obstructed and postponed so many times that the idea of a bilateral war memorial is little more than a distant vision.

The situation that I have outlined above does not, however, stop individuals from creating peace and war memorials without any permission or commission from the state or negotiating parties, and there are several examples where monuments were created by artists on their own initiative in Northern Ireland after 1994. One example is the artist Alistair MacLennan who has used the names of those killed in several of his performances and actions. In this article though I will focus on Irish artist Hilary Gilligan's intervention in public space entitled, "Our Trail of the Troubles”, that she made during Easter weekend, 1996.

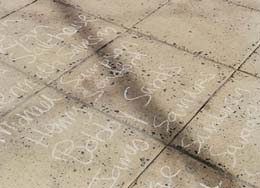

Equipped only with a list of over 3300 names of people killed on both sides in the conflict from 1969 to 1996, which had been published by a local daily newspaper, and several boxes of chalk, Hilary Gilligan started her work on Good Friday afternoon. She wrote down all the names from the list, one name on each line, ordered from a to z, with white chalk directly on the pavement on Royal Avenue, which is the central shopping street in Belfast. Over the four days it took her to complete the list she created a meandering line of names that ran from the front doors of the University of Ulster down the street some four hundred meters to Castle Court, the main shopping centre in Belfast. The result could be seen as a temporary war memorial, made by a private person, that was not sponsored or commissioned by any foundation or organisation.

Hilary Gilligan moved from Sligo in the Irish Republic to Belfast to study Fine Arts at The University of Ulster in the mid-nineties. Coming from the predominantly Catholic South she immediately found herself exposed to the segregating mechanisms that influence much of everyday life in Belfast, a situation she felt very uneasy with. In the spring of 1996 the newborn peace process came under immediate threat when the provisional IRA blasted a series of bombs in London to underline their dissatisfaction with the negotiations, and the political tension grew in Belfast. Both these factors plays important roles in the creation of "Our Trail of the Troubles".

I spoke with Hilary about that weekend over the phone. She is amazed that "Our Trail of the Troubles" still evokes such strong emotions and interest. In my opinion it is a very strong work. It has a political edge that you rarely come across, but is at the same time based on a personal engagement and a will to take risks to express something important. That engagement led her to create something that would have been impossible for the establishment during the circumstances.

Hilary Gilligan points outs some factors that contributed to the success of the event. Art students are often "getting away with a lot of things" as she puts it with a laugh, as they're seen as very innocent. She was not sponsored by any organisation involved in the conflict. She made sure that it would be difficult for the police to stop her by contacting them beforehand to get clearance for the action. Another key factor for success was the place and time she chose. The city centre of Belfast has been kept a mixed area throughout the conflict and both Protestants and Catholics celebrate Easter for the same reasons. As Good Friday is seen as a somber and mournful day, it was also a very suitable time to begin the intervention. The reader may respond that art in general is not an activity with any power to change the world, an objection with which I would only partly agree. Even though artists don't have access to governing powers they have access to a language that allows them to speak about and visualize what is possible, and that goes far beyond the sometimes narrow perspectives of real politics.

The image of Hilary Gilligan kneeling on the pavement, painstakingly writing down the names, must have been a disarming sight. Her work forced her to sit in a non-confrontational posture that definitely distinguished her from stiff drum-banging marchers, violent rioters and agitating politicians. She says she was terrified in the beginning, not knowing what reactions she would get. Belfast is a city where it can be very dangerous to cross the wrong border at the wrong time, and, aside from her boyfriend who took his time to watch over her, she was without protection. It was mainly because the situation was so unsafe that she started right outside the main entrance to the university.

It was therefore quite a surprise to her how well her action was received, and how kind people treated her, with only a few exceptions. People started discussions. Relatives of those killed searched for the names of their loved ones on the pavement. Others treated her to coffee and sandwiches. A lot of these were people that she, presumed to be a Catholic from the South, would never come into contact with in everyday life, such as Protestant ex-servicemen and policemen. She became, over those few days, a sight that people got used to, including the police. On the fourth day a police patrol car suddenly stopped on the side of the pavement and an officer leaned out of the open window and asked her, "What letter are you on now?"

On the fourth and last day, however, things might have gone terribly wrong. That Easter Monday there would be several Protestant loyalist marches in the city. These marches, which take place in the spring and summer, are a Northern Irish phenomenon that creates extraordinary tension between Catholic nationalists and Protestant loyalists, and often escalate to violent riots that can go on for days or weeks. The night before there had been rioting in the predominantly Catholic area of Ormeau Road and there was tension in the city where people were awaiting the marches and prepared for the rioting that could follow. For Hilary, this tension and anger hit her in the form of an aggressive and quite belligerent man who started to harass her, accusing her being sectarian and bigoted, all the things she was clearly opposing in her work. He was spitting on the ground beside her and she felt threatened but avoided starting an argument with him and he eventually disappeared. She continued her work and was getting close to the end of the list of names when a gang of young boys approached her and warned her that a loyalist Apprentice Boys march was on its way, and would pass her in a few hours, and they told her that she might get into trouble if she wasn't gone by then. But by the time the march arrived at the city centre, Hilary had completed the list of names.

Hilary Gilligan's intervention in public space shows that you don't have to wait for a government's decision or a very slow peace process in order to create a bilateral war memorial. In the case of this particular intervention, the memorial was appreciated among people tired of bigotry and violence, in part because of the event’s temporary character and the artist's choice of materials, time and space. Another successful example of a private initiative from the U.S. is "The Wall that Heals", which is a mobile miniature replica of Maya Ying Lin's famous "Vietnam Wall" in Washington. The first version of The Wall That Heals was made by a veteran, who built his replica in foldable sections so that it could easily fit in a truck, and then started to tour the U.S. with it. The memorial became a huge success and has developed into a well-funded organisation with several replicas constantly on tour.

What is so exceptional in the case of Hilary Gilligan's work, as with other similar works made by Northern Irish artists, is its bilateral side. It is one of the very few successful bilateral war memorial that have been made in the Western World after World War II. This, unfortunately, says a lot about how unwilling we humans are to consider "the others" themselves as human beings, and to seek solutions to conflict, rather than to fuel conflict.

***

Hilary Gilligan is a visual artist who was educated at Ontario Collage of Art and Design in Toronto, Canada and University of Ulster in Belfast from which she has a Master of Fine Art. She currently lives and works in Sligo, Ireland. For more information about her work, please download this PowerPoint presentation (8,9 Mb). All images on this page are copyright protected and courtesy of the artist Hilary Gilligan.

***

NOTES

(1) Jane Leonard writes in her report "Memorials to the Casualties of Conflict: Northern Ireland 1969 to 1997" that "The cease-fires inaugurated a vigorous public debate on suitable forms of commemorating the casualties, issues and lessons of conflict. A national memorial was proposed within a few days of the IRA cessation of violence in August 1994. /.../ In November 1994, the Irish Times columnist, Fintan O’Toole, suggested that the ‘task of imagining memorials that do justice to the memory of all the victims of violence from all sides might help to unlock the imaginative sympathy that will be so necessary in the coming months’. The early months of the cease-fires stimulated a widespread debate on forms of remembrance in Northern Ireland. Peace also facilitated previously taboo commemorations."

READING:

1. Memorials to the Casualties of Conflict: Northern Ireland 1969 to 1997

by Jane Leonard (1997), ISBN 1-898276-16-1 Paperback 38pp

Community Relations Council Resource Centre

http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/commemoration/leonard/leonard97.htm

Part of the series ''Issue #1''

The first series of features presented on war-memorial.net